|

There are “lumpers” and there are “splitters.” Some fisheries scientists think that largemouth bass and Florida bass should be split into two species. Others lump them together as one species as mere diverging strains or races. This much can be agreed upon: bass in southern climates grow big, and fishery managers are careful to conserve the trophy fish coveted by anglers at all experience levels.

To that end, Summer Lindelien, a fish biologist with the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission has endeavored the last four years to learn more about how Florida’s largemouth bass, Florida bass, and their hybrids grow over time. Excise taxes paid by fishing tackle manufacturers and on motor boat fuels fund her research in grants administered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Wildlife and Sport Fish Restoration Program.

The research is bearing fruit that promises to yield better bass fishing in Florida—if not anywhere the 19 species and subspecies of the black bass family swim. More research is in the works and necessary to take further steps.

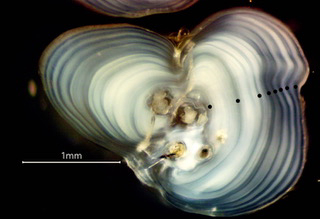

Lindelien and her FWC colleagues are developing a new method to determine age and growth rates of trophy largemouth bass that would otherwise be missing in population assessments and ultimately, fishing regulations. Hard bony structures are best for determining a fish’s age, body parts such as scales and ear bones that put down rings at each year of growth. The latter is most reliable but there is a downside: it is 100 percent lethal. Dorsal spines may be the alternative. The method shows great promise as Lindelien learned while a graduate student at the University of Florida. She and her colleagues also completed a six-waterbody study to refine the efficacy of reading age rings on dorsal spines and are in the midst of evaluating how dorsal spine ageing error affects population dynamic metrics.

|

Lindelien and colleagues caught wild bass known to be hybrids of largemouth and Florida bass, 36 fish in all, varying size from 12 to 22 inches long. Six bass each were acclimated in six tanks and three from each tank where randomly picked to have three dorsal fin spines extracted with surgical scissors and snips cut flush with the bass’s back. The fish were monitored for injury and mortality for 35 days afterward.

None of the bass with missing spines perished. Overall condition between fish with spines intact and those with spines removed did not vary to any great degree at the conclusion of the month-long study. In the end, the method shows much utility as a means for black bass fishery managers to gather more data on trophy fish without deleterious effects on the fish and the fish population. The method also holds promise down the road for citizen-scientists—anglers, that is—to weigh and measure and trim a spine before releasing trophy fish, thus greatly expanding the essential data scientists need.

Lindelien is the first to confirm that removing dorsal spines is benign to largemouth bass. According to Lindelien, as the dorsal spine aging technique is refined it might be employed on other black basses, common and otherwise: Guadalupe bass in Texas, spotted bass in Kentucky, Neosho smallmouth bass of Oklahoma or the rarer Choctaw bass of Alabama and Florida where removing fish of any size is not an option.

Lindelien and her colleagues published the results of the spine extraction research in the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Journal of Fish and Wildlife Management.

-- Craig Springer, USFWS – Wildlife and Sport Fish Restoration Program