By Frank Sargeant

Frankmako1@gmail.com

Both my biggest ever seatrout, just under 30 inches long, and my biggest snook, just under 40 inches, came from the Indian River Lagoon (IRL) near Stuart, Florida. My guide in each case was Mark Nichols, founder of DOA Lures, and my lure in both cases was a DOA Bait Buster soft plastic mullet. Both were caught wadefishing in water less than knee deep.

It’s not that I was a good fisherman. There were just a whole lot of big fish in those waters some 30 years ago, and if you were slow and quiet and had the right lure and fished it the way Mark told you, you could get lucky with some frequency.

They don’t often catch fish like that there anymore.

The reason is not overfishing. It is water quality. The IRL, 146 miles long, stretching from Volusia to Martin County, has had a disastrous plunge in water quality due to a combination of the discharge of billions of gallons of high-nutrient fresh water from Lake Okeechobee, runoff from too many new housing developments and the incipient seepage of thousands of septic tanks from older residences very close to the water.

The elements reached critical mass about 20 years ago and the fishing has not been the same since. The once crystal clear water turned a sickly green, vast swaths of sea grasses died out, and the fishery virtually disappeared. Manatees in the area nearly starved due to the lack of sea grass.

But there’s life in the old girl yet.

After a decade of new regulations, cash infusions and better water management, the IRL is showing some signs of a comeback.

A combination of state funding, St. Johns River Water Management District-led and local government projects, and growing awareness of the lagoon’s challenges among residents and leaders are all helping to ensure the lagoon will again become a magnet for anglers, boaters and anyone who enjoys clean water.

The District has partnered with other agencies, including the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), local governments and water utilities to design and build tailor-made projects to restore degraded water bodies, including the lagoon.

Some of the recent work has included dredging nutrient-rich muck from lagoon tributaries, including the Eau Gallie River, purchasing and preserving land in conservation areas, and awarding nearly $40 million for cost-share projects in lagoon communities, leveraging $81 million in public dollars when combined with local matching funds and state funds from DEP.

Since fiscal year 2020–2021, the state has committed more than $100 million annually for water quality improvement projects, with almost 50 percent for projects in the lagoon. These projects and the funding are having measurable impacts on the lagoon.

It seems to be working in at least part of the system. The Mosquito Lagoon, the north end of the IRL, has seen the largest regrowth of seagrass in recent years, where mean percent coverage increased from 6.5% in summer 2022 to 20% in summer 2023. Nutrients are expected to continue to decrease.

Among the newest projects in the lagoon region are the C-10 Water Management Area (WMA) and the Crane Creek / M-1 Canal project.

A 1,300-acre stormwater treatment marsh proposed for Brevard County will reduce nutrient loads to the lagoon by treating the canal water, restore historic surface water flows back west to the St. Johns River, increasing flood protection and also providing angling opportunities.

The Crane Creek / M-1 Canal flow restoration project will redirect treated and cleaned stormwater from 5,300 acres to the St. Johns River The added flow of clean fresh water is expected to benefit the river, and getting that water out of the lagoon should also be a huge benefit.

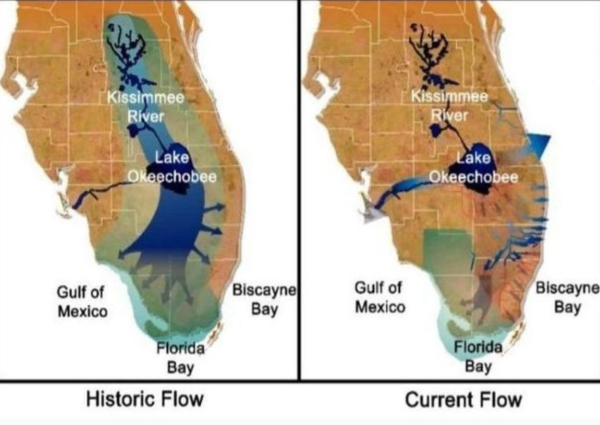

Multiple other storm water projects are in the works. In addition, groups like Captains for Clean Water (https://captainsforcleanwater.org) continue to fight for the rapid progress of the “Move the Water South” initiative, which will send over-enriched water from Okeechobee south through the marshes of the Everglades where it’s needed, rather than east and west to the coast where it causes disastrous algae blooms. (As this is written, there’s considerable release to the St. Lucy River, which goes to the IRL, but in general the progression has been positive in recent years.)

It took many years for the Indian River Lagoon to lose its spot as one of the nation’s premiere coastal fisheries, and it will take many years for it to be fully restored. But at least the arrows now seem to be pointed in the right direction, and both the public and the politicians in Florida seem dedicated to getting it right.