There’s been a surprising number of rip current deaths on coastal beaches this year, probably not coincidental with the excessive heat. The more folks who head to the beaches—many with little experience in ocean swimming—the greater the risk.

The north Florida area has been particularly dangerous the past week, with four young people dying off the beaches of Panama City.

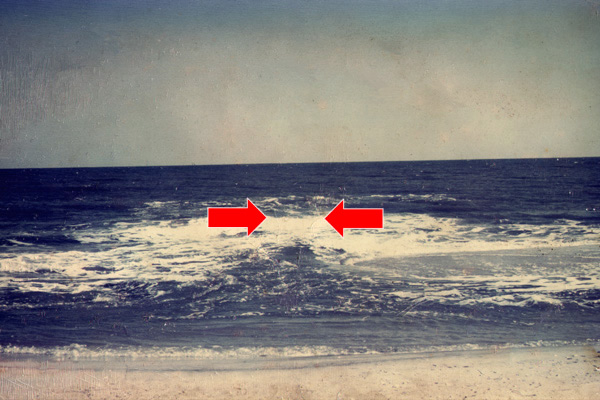

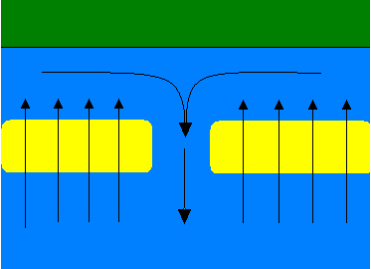

Oddly, the very thing that surf casters seek is what is so deadly to swimmers. A “rip current” is the stream of fast running water that flows out of a break in the nearshore sandbar, where all the thousands of waves that hit the beach release the huge volume of water slamming into the shore. They form mini-channels in the bar, and when waves are large, so is the outflow—dangerously so.

The rips are so strong at times that they scoop up sand fleas, crabs and minnows and send them seaward, attracting predator fish, which is why anglers avidly seek them out. But what’s good for anglers is very bad for swimmers.

While swimmers might think they’re safe by staying in water no more than chest deep, a strong flow and the roll of the sea can lift and carry you quickly into deeper water.

While a strong swimmer who keeps his/her head can easily get out of a rip, most of the visitors to the beaches are not strong swimmers, in the sense that they can’t do several hundred yards in rough water. Most of us who are not competitive swimmers never have cause to swim a distance, and never have the experience of battling large waves.

The rip current can run for hundreds of feet seaward when waves are large—usually on a south or southeast wind on Florida’s Panhandle beaches. It’s basically like stepping into a fast-flowing river, and there’s no way for even a good swimmer to progress shoreward against that flow.

Fortunately, the individual rips tend only to be about 50 feet wide on Gulf beaches, so for those who understand the situation and swim parallel to the beach in either direction, escape is possible. But it must be done quickly, before the rip carries you out beyond your capability to swim back. Once you clear the seaward flow, you’ll have the waves at your back, and those at home in the water can even make use of the push to assist them shoreward.

Particularly dangerous in rips are floating devices, which can give swimmers a false sense of confidence. The tube floats and rafts can quickly carry a rider far offshore in a rip, and they are very difficult to paddle back towards shore even if you escape the rip flow.

Most public beach accesses in Florida go by the warning flag system, where one red flag means there are rip currents and swimming will be dangerous, two red flags means you can get a ticket if you are dumb enough to go in the water with strong rips running. Many of the people who died in North Florida last year ignored double red flags, per rescue agencies.

A separate issue is the tidal currents around inlets—on falling water, these strong flows can quickly carry an unwary swimmer miles out, while on incoming they can sweep a swimmer out into a large bay. These flows are particularly strong around the new and full moons when tidal changes are greatest. But they are easily avoided by simply not swimming near inlets.

To be sure, the beaches of North Florida are usually safer than those on the Atlantic Coast because the waves are typically smaller. It’s only when sustained winds build big surf that the dangerous rips form. Note, though, that it doesn’t always take lots of local wind to build enough waves to create a rip—a tropical or hurricane passing far offshore can create serious rips, even though winds at the beach are moderate.

The easy way to stay safe is simply to keep an eye out for those warning flags—and to obey them, every time.

— Frank Sargeant

Frankmako1@gmail.com