In the military, it’s commonly accepted that “generals fight the last war.”

Strategies are usually based on the last war, not the next one. Unfortunately, that’s often proven true as tactics evolve following setbacks.

During my recent trip to Gunsite Academy, Michael Bane made a statement that, brought the soldier’s lament home: “The whole world changed in 2019. We’re training for the wrong fight.”

In his new world, seldom will you see a random attacker. Since 2019, multiple attackers have become more common than lone assailants-with the exception of lone-wolf crazies who attack places, not people.

“We’re still training to stop an individual,” Bane said, “we need to be training to identify and defend ourselves against multiple attackers -it’s the way the world works anymore. There are packs of attackers.”

I wanted to wait a bit and consider his assertion before writing about his assertion. After a few days reflection, along with reading and watching local news, I’m afraid Michael is -once again- onto something.

In the local news I’ve forced myself to watch, there were eight violent attacks reported. In seven, there were multiple attackers

So what’s that mean for people?

We commonly train on square ranges, grooving a “shoot the drill then holster carefully” mentality. We’ll, that keep your “head-on-a-swivel” thing isn’t just for “operators” or fighter pilots.

Neither is the OODA loop. Everyone needs to be prepared to observe, orient, decide and act faster than ever before (yes, that’s the “OODA” loop).

That means paying attention to those “uneasy feelings.” It means living like a sly fox, not a frightened rabbit. Being aware of our surroundings and being ready to move.

NOT like someone headed for the OK Corral. Just someone who knows where they’re going and is headed there purposefully.

Nose out of phone.

Head out of the clouds.

Mind on what you’re doing. Living in the now.

It’s the kind of preparation that chooses to walk away, not escalate. That withdraws instead of engaging until there’s no other option; then acting decisively to end the threat.

In other words, choosing not to fight until you have no other choice -then ending the fight quickly. “Ending” does not mean shooting someone to slide lock or until the cylinder’s empty. It means until the threat isn’t threatening.

Living like you won’t become a victim without putting up a fight.

You know the expression: “If you don’t want to get eaten, don’t look like food.”

Unfortunately, your responsibility as a responsible citizen won’t end if/when the attacker’s no longer attacking.

To me, that seems to be the place where we’ve left a huge gap in our training. We train like hunters not humans. If we’re hunting, the goal is simple: a clean, quick, one-shot kill.

Self-defense doesn’t work that way.

Not every confrontation will end in bloodshed. Not every confrontation with gunfire will end with no one needing medical assistance. In fact, that scenario may end with everyone involved needing medical help.

That’s where it seems we’re missing the boat. We characterize ourselves as law-abiding citizens who only fight when forced to. We are peace-loving citizens otherwise.

But I’d argue that when you carry a gun, you carry more than the responsibility to use it wisely. You also carry the responsibility to help after the gunfire ends. In combat, soldiers are taught to shoot the enemy. But when the enemy stops being a combatant, the soldier -sometimes the one who inflicted the wound- goes to work attempting to save that person’s life.

Don’t know about you, but I’ve never had any sort of training transition from a shooting scenario into a first aid drill. But I have faced the frustration of being in a real emergency situations where I knew I wanted to help, but lacked the knowledge to do anything substantive.

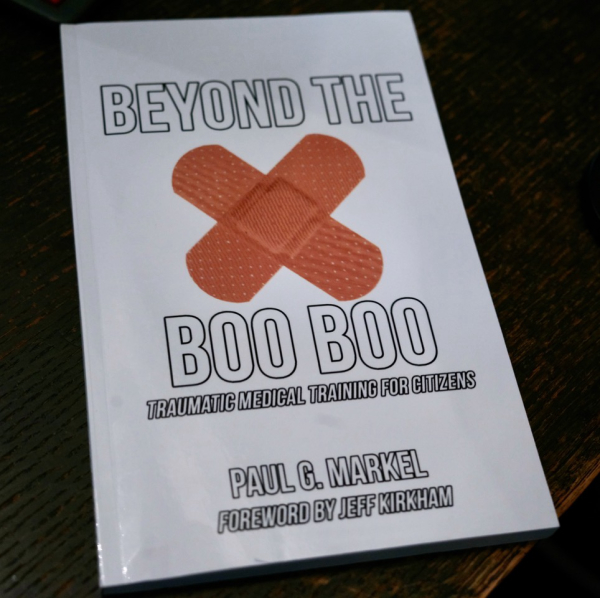

Since reading a book called “Beyond the Boo-Boo” (Traumatic Training for Citizens) by my friend Paul Markel, I’ve changed how I think about my responsibilities as a gun owner. In his book, Markel makes a great point when he says “If we can train 18 and 19 year old kids to save their buddies’ lives on the battlefield, why can’t we teach the average citizen to save lives on city streets, in workplaces, and in the home?”

He offers this sobering answer: “The answer to that question is that we can train citizens to save lives, however, for far too long we have chosen not to.”

Before you start talking about opening yourself up to lawsuits by trying to help, note there’s a big difference between helping apply direct pressure to a superficial cut with a dirty handkerchief and saving someone with an arterial cut squirting blood with every heartbeat.

One is a “boo boo.” The other is a “blowout.”

You can survive a boo boo until help arrives, but a “blowout” can mean death in minutes -including the minutes before you realized it was a desperate situation.

Most first aid kits won’t have the tools to handle a major medical situation.

But a little knowledge can help you improvise a short-term solution that works until the professionals do arrive.

There have always been some very basic first aid supplies in my backpack. I’ve added a tourniquet to the outside, along with a roll of gauze and an Ace bandage in a baggie to the inside. They add a few ounces of weight, but could make a disproportionate difference in the outcome of an emergency.

Guess my definition of “personal defense” has expanded. I’m OK with that.

— Jim Shepherd